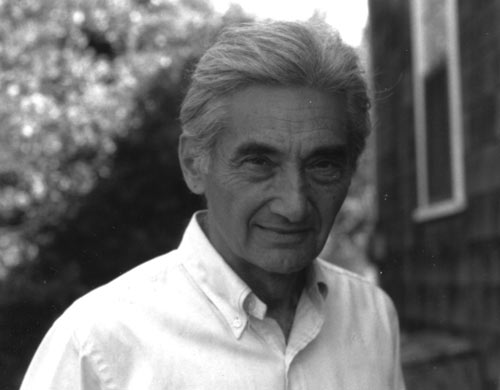

It’s funny how you can read or see something, and suddenly you start noticing references that you would have completely overlooked beforehand. As I wrote a couple weeks ago, I read Howard Zinn’s provocative A People’s History of the United States this summer. Now, almost everywhere I look someone is paying tribute to Zinn or invoking his famous book.

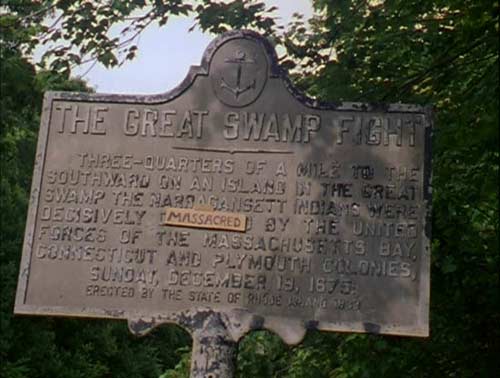

The latest example is the hour-long video Profit motive and the whispering wind (lack of capitalization is intentional). Directed by film curator and scholar John Gianvito, it explicitly echoes Zinn in its attempt to reawaken our grasp of progressive history and the heroes who blazed the trails before us. Gianvito accomplishes this by shooting gravesites and other markers of memory all over the United States. Some are tombstones of famous people: Henry Thoreau, Harriet Tubman, Cesar Chavez. Others are less well known, though history fans and readers of Zinn’s book will recognize the names of Anne Hutchinson, Daniel Shays, and Eugene Debs, among others.

Although some footage of signs detailing labor strikes and battles will inform those who don’t already come with the necessary background knowledge, Gianvito provides little context for his shots, obviously believing that merely recalling the dead will honor them and provoke the viewer to find out more. There is an implicit trust in the audience, which has inspired some critics, but I couldn’t help wondering whether most viewers (at least those not already part of the “choirâ€) would just find the exercise baffling and unproductive. Admittedly, there’s little of the patronization that comes with PBS documentaries, but there’s little of the information either.

Not that providing information need be a primary goal, but the movie’s formal structure is also wanting. Intercut with the 3-5-second shots of gravestones and other markers are repeated shots of nature, specifically wind blowing through the trees. Gianvito has spoken of his pantheistic perspective, but there’s little rigor to his choices. I have no idea why he chooses certain locations and times for the trees, and I fear Gianvito doesn’t, as well. And certain motifs pop up (decaying tombstones, signs of big business) only to disappear as if Gianvito had an idea but then got distracted by something else.

Several critics have invoked James Benning, but Benning’s editing is much crisper, much more intentional. A cynic might wonder if Gianvito edited his nature shots by picking them at random. I’ll admit the film creates an almost hypnotic effect as it reaches its conclusion, with the pleasant use of ambient sound washing over the audience. And it has its heart in the right place. But if you didn’t know who Sojourner Truth was (or others like her) before you came in the theater, I can’t imagine that this movie will have any impact on you.